The Future Through the Lens of Connect To Learn Scholars: Participatory Photography in Mbola

Posted: August 12, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentFollowing up on our poetry workshop, I returned to Ilolangulu Secondary School to further explore our final brainstorming question—“How do you want to be seen by the world?” The aim of participatory photography is to place visual training strategies, along with cameras, in the hands of those more likely to be in front of the lens than the force creating images behind it.

We began by learning photography basics, including framing (landscape or portrait), and vantage points. Using an iPad, we looked through a series of photographs as a class and determined where the photographer was standing to capture the image. Choruses of “Bird’s eye view!” “Worm’s eye view!!” “Close-up!!” echoed through the classroom’s open windows. Looking through another set of images, we discussed the ways the photographer had worked to evoke emotion from the viewer. Students identified whether the images felt sad, surprising, funny, happy, or angry. We discussed, in both English and Kiswahili, what made the images feel that way. Was it the colors? The facial features? The vantage point?

The conversation then shifted back to the way students wished to be seen by the world. When we had discussed this in the initial poetry brainstorming, students gave examples that pointed to their future careers—doctors, presidents, and educators. We discussed the attributes that they would need to excel in these fields, connecting back to how those same attributes serve them today as scholars and will help shape their path toward their dreams.

Moving from abstract to concrete, I asked each student to close their eyes and imagine what an image of themselves that contained all of those dreams and attributes would look like. I passed blank paper out to each student with instructions to draw a rough sketch of that image, including the vantage point, emotions, and framing. They were to select their setting (from options around the Ilolangulu Secondary School campus) and what they wanted to be doing.

Armed with their sketches, we bounded out of the classroom to begin snapping portraits. Because students had drawn their photo as they wanted to be portrayed, they handed their sketch to another student who framed and shot each portrait as it had been drawn. Students each took turns holding the heavy Canon 30D, peering through the viewfinder and pressing the shutter, capturing images of their friends and classmates.

Students surprised me with their creativity; the props they used, the parts of campus they brought me, and the poses they dreamed up were terrific and far better than I could have found.

Laughter rang out across the campus that afternoon as students checked their images. Shy smiles gave way to happy shouts while students figured out the digital single lens reflex camera. After each shot, girls crowded around to see how it turned out. By the time we walked out of the school gate, sweaty and dusty, each student held their heads a bit higher. I asked Lucy Jamek, a Form 1 student, what she thought of the day as we bid the school grounds adieu.

“I felt like my dream. I felt like someone who was important, like the intellectual I hope to grow up to become. When I get there, I know what it will feel like, and what the smile on my face will look like. Today was good.”

Defining Moments

Posted: August 9, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized 1 CommentIn my final Community Education Worker interview (38 open-ended questions? What was I thinking???), I concluded in my usual way by asking if there were any questions or ideas that they wanted to share with me. Catching me offguard, I was asked for a working definition of education, written in English for the CEW to take home, translate, and think about.

While working to establish the Education Collaborative at Columbia University last year, colleagues and I spent a couple of afternoons chewing through the semantics of education– what it means, what it should mean, what it includes and excludes. We all have our own working definitions of many of the concepts we face every day; I’m pleased to say that my Education Collaborative experience helped me to form my own definition in relatively short time:

He was pleased with my work, although he may well have words to add or subtract once he has translated it completely. As I prepare for my wrap-up presentation on my work across Mbola MVP’s education sector, I’m wondering who among my darling readers can help me improve this definition. Thoughts?

Guest Blogging – Connect To Learn

Posted: August 7, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentI had the honor of blogging for education and technology NGO Connect To Learn this month– check out more:

Tales from Tanzania: Exploring Poetry and Identity in Mbola

Posted Mon Jul 23, 2012 by Debi Spindelman

Making the long and bumpy ride out to Ibiri Secondary School for the first time, I was rewarded by the sight of bright happy faces and the smart maroon-and-white uniforms worn by MVP Mbola’s secondary students.

Armed with my camera, a ream of paper, and translated copies of poem samples I set out on my task: to lead a brainstorming session and poetry workshop with Connect To Learn scholarship students about identity and the way the opportunities surrounding them have shaped their dreams.

We began by brainstorming all of the labels associated with who each student is–daughter, brother, pastoralist, Muslim, student, scholarship recipient and more. Students impressed me with the variety of ways they see themselves within their family and beyond. We moved on to what it means to be those things in their village, as well as the ways they interact with technology in their lives.

Students brainstormed the role education played in shaping their dreams for the future, and their reasons for reaching toward educational attainment in secondary school. I was impressed and interested to learn that all the students present that day dreamed of becoming doctors, all for very different reasons. We concluded by discussing where students look to find hope for their future and how they wish to be seen in the world, both now and in the future. The students were both insightful and comfortable opening up about their family backgrounds and the challenges they have faced in their journeys thus far.

Here is Rozalia, in her own words:

I am Rozalia Pastori

I am from Ibiri village

I am fifteen years of age

The first born in my family

We are only two children still alive in my familyI smell food crops growing

I hear the voices of birds, people, and cars going past

I see birds, cars, trees, and livestock animals

I eat ugali, beans and fruits

I sense things on my body like insects, the heat of the sun, and coldI have seen phones and computers

I have used a radio

Also solar lanterns, cars, motorcycles and bicycles

I have seen so many different things

Things like trees, people, and birdsPhones make my life better because of the communication they offer

Solar energy is used to produce light

Light which is used for studying and charging our phones

Computers are used in my life for storage

To store materials and notes for future generations and eyesI am taking three subjects

Because they are the ones I understand

Those subjects are biology, chemistry, and physics

I also learn the laboratory rules

I learn to provide the first aidI am studying to become a doctor

In order to help people

Also to get higher education

And to get a good job

So I can earn money easilyI get support from our teachers

I also get support from my parents

Also support from different relatives

Like my sister who is a nurse

And support from myself

Debi Spindelman is an MPA-Development Practice student at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. She is spending this summer performing a field placement in Mbola, Tanzania. Working closely with the education sector on a number of initiatives, she is also photographer and former teacher with an interest in participatory research methods.

Why I Delay Pregnancy

Posted: July 17, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentBuilding on the success of Laura Budzyna’s Mambo Safi Club, one of the action items for education in 2012 is a series of forums and clubs at secondary schools focusing on sexual and reproductive health and the prevention of gender based violence and discrimination. While involvement in this was not originally part of my game plan for this summer, these topics are of great interest both personally and professionally, and I retain a deep interest in the way these topics play out in rural Tanzania when compared to Kenya and California.

Teenage pregnancy is one of the biggest reasons for girls to drop out of the cluster’s two secondary schools. As a graduate of Vista High School, the irony of this current situation is not lost on me. (For those not familiar with that corner of North County San Diego, girls started dropping out of my classes to have their first child in seventh grade. Mad props to those running the teen parenting program at VHS that allows students to return to classes after maternity leave, offering childcare on campus in exchange for one class per day in the child care class, learning parenting and life skills, thereby offering these young moms and dads a chance to complete their diploma and offer a better chance at life to their kids.) Lacking these safety nets, pregnant girls in Tanzania are summarily expelled, never to return to school again. The solution? Keep this from happening.

In the more remote villages, parents are afraid to send their daughters to school because they’re convinced they will come back pregnant. This isn’t terribly far-fetched, as girls are abducted on the route to and from school with alarming regularity, and the “supervised” boarding facility set up a few years ago for secondary school girls to keep them safe far from home resulted in pregnancy in 8 of the 12 students who were part of the pilot. Okay, keeping girls out of school is an option I suppose. But collectively, can we do better? I think so.

Enter the Jitambue Club. Emerging from a morning brainstorming session fueled by andazi, sambusas, and chai rangi, jitambue is Kiswahili for self-knowledge. Over the past couple of months, the community and gender team have visited secondary schools to provide basic reproductive health education and pregnancy tests to adolescent girls in a somewhat ad-hoc manner. Formalized this month, the Jitambue Club will provide regular encouragement to focus on the long-term—hopes and dreams, not 5 babies before reaching 23.

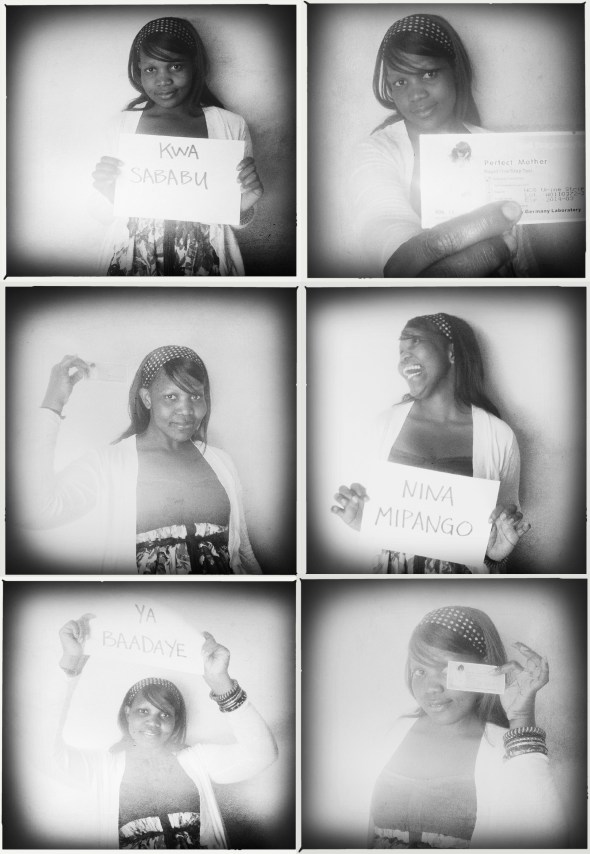

One of my smaller side projects is to work with this club to use creative visuals to remind students of these long-term plans. Borrowing from a condom-use project aimed at LGBT youth in San Diego, my project uses photography and a bit of creative writing to answer the questions “Why do I use condoms?” and “Why do I delay pregnancy?”

This project is expected to launch next week, so I put together a series of test shots with my darling friend and MVP Community/Gender Coordinator (and Acting Education Coordinator) Juliet about her reasons for delaying pregnancy. For those whose Kiswahili is still as bad as mine, it says “Because I have plans for my future.”

I’ll need to use a better editing software and perhaps not black and white for the student images (that’s a pink pregnancy test in her hand), but I like how it’s coming together. Images will be stitched together for each of the participating students, then printed and sent home with them to post either in their classroom or at home to keep those hormone-soaked eyes on the prize.

So… why do you delay pregnancy/use condoms?

Mapping Vulnerability: Facing the Tough Stuff

Posted: July 16, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentTransport out to the villages is a tricky thing; there are limited vehicles, limited drivers, and limited daylight to contend with. The best way to get where you need to go, and meet with the people you wish to see, is typically to jump into one of the white MVP Land Cruisers or, if the fates frown upon you, the cluster’s sole ambulance (which lives in at MVP headquarters in Tabora) along with several other people headed in roughly the same direction. As the Community/Gender and Education sectors often work closely together, I have joined community and gender facilitators as they met up with CEWs in their home villages to conduct a rapid survey of the most vulnerable households in the cluster. Walking from house to house, we spoke with the poorest families in this remote corner of Tanzania, grappling with the most difficult situations in the entire village cluster. Elderly couples with no safety net to protect themselves, who had nonetheless taken in multiple children who had lost mothers to AIDS. Women younger than me with seven children, each born less than a year apart and pregnant yet again, with absentee husbands unwilling to support the growing brood. Nine year old heads of household, living in a larger compound with other food-insecure families looking after them as they can.

These are the stories of poverty that, according to some narrative threads, define the African continent. I have a strong distaste for this narrative thread, as those who have never visited but only seen images of babies with distended bellies and flies in their eyes can be misled to believe this is a hopeless place, mired in its own failure. This narrative is extremely limited, of course, and its brightest critics have given this problem of representation without dignity much more articulate criticism than I can muster.

As a photographer, I work to share the hope, the struggles, the dignity and the humanity of those I meet across the globe. In the best cases, I am afforded the opportunity to sit down with those most likely to be in front of the camera lens—not behind the lens creating the images that move us– and teach them the basic photography and visual literacy skills needed to construct their own piece of the narrative. Postmodern anthropologists tried their hardest to climb inside the perspective of those they wished to study to see the world through their eyes; as a development practitioner grounded in anthropology, participatory photography is one of my favorite tools.

Until my participatory photography workshop happens (next week? The week after?), here I remain. And the best way to spend time with a Community Education Worker in her own village is to come along on these household visits as MVP-Mbola gets a handle on who exactly needs social supports the most. So the images that follow are NOT fully representative of the reality faced by all Tanzanians. However, they do capture moments in the heartbreaking reality of many whom the government and NGOs have failed and continue to fail. Informed permission from subjects and guardians was negotiated in each image. It is my sincere hope that the documentation of this reality helps trigger a shift for the most vulnerable members of this region.

Quite possibly the oldest woman in the village cluster, 103-year old Mwayuwe shares her dental situation jokingly with MVP Community Facilitators. Here they compare teeth while Mwayuwe relaxes at home, cared for by her daughter.

Interwebs Diplomacy

Posted: July 16, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentApologies for the radio silence, my friends. There have been some wonderful HR decisions made recently in light of emerging concerns in the Education Sector that are best left off-line. MVP Mbola has taken actions that reassure the reader (and writer) of their dedication to the children of the village cluster and their educational future. With that, we’re back in business!

6/6 Mbola and Ilolangulu Villages: First Impressions

Posted: June 18, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized 1 CommentFor our second day of work, the intrepid team of Danielle Sobol (Agriculture-Business), Vinay Krupadev (Community Health) and myself (Education-Gender) jumped into one of several white MVP Land Cruisers and set out for the field. We accompanied several key staff members and seven candidates in the final interview round for a newly created Communications Assistant position. Easily the most intense interview situation I’ve ever seen, it also proved an excellent hands-on introduction to several of the development sectors addressed by the Millennium Villages Project-Mbola.

Before joining the crowd, I had the chance to drop by a small community center to introduce myself to most of the new Community Education Worker team. Similar to the Community Health Worker concept, Mbola has selected 10 paid volunteers who have been nominated by community leaders to undergo training to support educational outcomes in the small communities where they reside. This project is in the pilot phase in the Mbola cluster, and my primary project for the summer will be a process evaluation of their training and implementation at the pilot level. They underwent a week-long training last month, and had been gathered for a brief computer-based learning assessment. I awkwardly read a Swahili introduction of myself and my interests before each Community Education Worker introduced themselves and the village they represent. Before we could get too deep, I was whisked away to join the grand tour. I sincerely look forward to getting to know each of them better, learning their motivations for joining this effort, as well as what they see as the top challenges and opportunities facing education in their village.

On the first stop of our tour, we were introduced to the Life Innovation Container, a converted shipping container retrofitted with solar panels and donated by Panasonic. Situated directly outside Mbola Primary School, the solar energy collected provides enough power to light classrooms and power a computer lab provided by Connect To Learn. Beyond academic uses, enough power is generated to support small enterprises such as cell phone charging. Cell phone technology has leapfrogged past traditional landlines to be the most prevalent communications technology in Africa, despite the lack of electricity in most homes. Thus, cell phone charging kiosks are an important microbusiness that allows people living in rural areas to connect to family and friends across the country, wire money to one another using M-Pesa technologies, and even receive farming information to support agricultural cycles. To prevent interruptions during the school day, business activities take place in the afternoons and evenings.

We left the school and ventured to a medical clinic deeper in the bush. I tried to ignore the looks from exhausted-looking parents who were no doubt wondering why the one doctor on duty was giving a tour and extended explanations to the crowd of visitors instead of attending to their clearly sick children. The doctor lives on the premises and is supported by a nurse team as well as dispensary workers. Rapid diagnostic tests were demonstrated to test patients for malaria, and outside a gaggle of brightly dressed children played patiently while their siblings waited for care.

Our final stop was a nearby warehouse that held harvested bags of dried maize and hundreds of bags of fertilizer that had been donated by Monsanto. Monsanto’s reputation across the globe is highly controversial, and the extent of its involvement with the agricultural sector of the Millennium Village Project was surprising. As the least agriculturally-involved member of our team, I will leave it at that.

My role in this extended interview tour was to provide photo documentation that would allow the Communications Assistant candidates to write a blog post and press release about what they had seen. Candidates got to choose from my images of all three stops to illustrate their written pieces and demonstrate their ability to communicate the progress being made in the Millennium Village Project to the Tanzanian press and global community. Most candidates selected the same images for their intensive two-hour writing period at the end of the day. They weren’t told ahead of time that there would be an assignment like this; truly an impressively intense interview tactic that made me wonder about some of the relatively cursory job interviews that take place back in the States. As of this writing I haven’t heard who emerged the winner from the 10-hour final interview, but we all boarded back into the Land Cruisers

While waiting for them to fervently complete their writing assignments, Danielle and I went for a walkabout following a trail that led away from the school to a newly constructed water pump. We stopped for conversation with three separate households, learning what crops they grew and discussing family life. Twice we were asked how much the ticket from New York to Tanzania cost; an interesting proxy inquiry into our economic status. We responded that our school had covered the cost, and we were here to learn from them. One woman asked if we were friends with Jeffrey Sachs, which we of course found highly entertaining. *

*As students at the Earth Institute and Columbia University’s MPA in Development Practice program, we will forever be linked to Dr. Sachs and his work advising the UN Secretary General on the Millennium Development Goals. As of this writing, we have yet to have an actual class taught by the man, but are crucified regularly by our friends over at NYU for being his lackeys.

What’s all this, then?

Posted: June 11, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Introductions, Millennium Villages Project Leave a commentHabari za leo from Western Tanzania! Welcome to my home for the next two months, and the online home of my thoughts and reflections during my summer field placement in the Millennium Village Project in Mbola, Tanzania. More about my projects in a later post. To begin, in case you haven’t been living and breathing each of the Millennium Development Goals for the past year as I have, I want to provide an introduction by someone much better paid than myself.

From the Lancet, a concise and well-balanced perspective on the Millennium Village Project:

The Millennium Villages project

Grace Malenga , Malcolm Molyneux The poverty in which a large proportion of the world’s population lives and the consequent unnecessary deaths of over 7 million children every year are scandals of our age. In 2000, global heads of state reached agreement on the Millennium Development Goals; how to reach, or even to approach, these goals has been the subject of much advice, debate, and effort since, with so far only partial success.In The Lancet, Paul Pronyk and colleagues assess progress towards these goals in the Millennium Villages project. The report outlines how village clusters (including nearly half a million people) in nine sub-Saharan African countries were selected, and describes the project’s intervention: the provision of financial assistance for a multidisciplinary development package costing around US$140 per person per year for 10 years, with the costs shared by donors, the villagers, and local governments. Pronyk and colleagues report the findings of an assessment covering the first 3 years of the project.Successes are reported in both process indicators (more people in the target villages now sleep under bednets, go to school, have access to clean water, are vaccinated, grow diverse crops, and can make money) and impact indicators (fewer children are stunted and fewer are parasitaemic). Above all, in the study’s primary endpoint, fewer children died before the age of 5 years (an absolute decrease of 25 deaths per 1000 births [95% CI 5—44] in the intervention villages over 3 years, and 30 fewer deaths per 1000 births [3—58] relative to comparator villages).The Millennium Villages project was devised as a proof-of-concept intervention,5 implying first that the consequences of the intervention can be measured (proof), and second that the intervention, once proven, has the potential to be applied where the same problems require attention (concept). In the case of the Millennium Villages project, both proof and concept have generated extensive and often very heated debate.In the original design of the project, no comparator villages were included, partly because of the ethical difficulty of monitoring control villages over many years without offering their communities any benefit.Without comparator villages, proof of efficacy would have to depend on before and after comparisons within the project villages. Such comparisons can be misleading, as illustrated when the project seemed to take the credit for a steep rise in mobile-phone ownership in project villages—it was quickly pointed out that the same increase had occurred in many non-project villages in the same countries.For the present assessment, however, comparator villages had been chosen; these control villages were matched to project villages in as many relevant characteristics as possible, so comparisons could be made. This design is not optimum, because allocation to intervention or control was not randomised initially and prospectively, and because baseline data are, therefore, not available for all indicators in the control villages. Comparisons with national and regional trends have also been made, but the value of such comparisons is limited by the fact that the villages are not strictly representative of the wider area, having been chosen for their poverty.The concept being tested in the Millennium Villages has been as vigorously debated as the proof. Will it be possible to continue the new activities in the project villages after the end of the project (is it sustainable)? Could the same interventions be applied to the huge number of comparable villages throughout sub-Saharan Africa (can it be scaled up)? Perhaps a more difficult question has been whether an intervention of this kind inherently stimulates local capacities, or does too much of it consist of external support that might induce passivity? The project planners point out that high-income countries have pledged enough money to provide the finances for a long-term scale up, If those countries would only fulfil the pledges made at Gleneagles, UK, in 2005—pledges that have so far been more honoured in the breach than the observance. The Millennium Villages project also emphasises that its interventions work through local communities and with local governments, aiming to empower them to increase self-dependence—that the package of assistance is a hand-up, not a hand-out, and that external aid will gradually diminish over the second half of the project.The Millennium Villages project is not perfect, and nothing with its objectives could be. What is certain is that the project will not have been a success if it merely improves the statistics in its target villages, any more than a clinical trial is useful if its benefits are confined to the trial participants. A global opportunity now exists to learn and apply the lessons emerging from the Millennium Villages. Seizing this opportunity will be the joint responsibility of all of us, including individuals and governments of high-income countries and villagers and governments in developing countries.Several aid programmes have resembled the Millennium Villages project, although on a smaller scale; many have flourished briefly but ultimately come to little because either local or international commitment waned. It is urgent and crucial that we turn the Millennium Villages project to good purpose. This project can be a catalyst for converting the Millennium Development Goals from nice ideas into achievable objectives.